India is known for its rich cultural traditions, and its diversity is reflected in a wide variety of unique and remarkable art and craft forms. These are an integral part of Indian identity, but over time, many of these traditions have faded into obscurity. One such art is Tikuli, a form of hand painting that dates back more than 800 years. Once vibrant and flourishing, this art has now become a neglected and vanishing craft.

Tikuli art, a lesser-known but richly vibrant form of painting, originates from the culturally abundant state of Bihar, India. With a history that spans centuries, this exquisite form of artwork is deeply rooted in the traditions of Mithila and has evolved to carry layers of historical, spiritual, and social significance. What makes Tikuli art especially fascinating is not only its aesthetic appeal but also its unique journey of revival through changing economic circumstances and even through challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic.

This Article, titled “The Revival of a Dying Legacy—Tikuli Art”, is a sincere attempt to highlight the importance of reviving such a heritage craft. It aims to give new life to Tikuli by exploring innovative ideas and techniques that can adapt the art to contemporary needs. Through commercialization and modern product development, the goal is to provide new livelihood opportunities for artisans while preserving this traditional art.

INTRODUCTION

Tikuli, a local term for “Bindi,” is a dot that signifies a woman’s commitment to her husband and is worn by royal married women in Bihar. The Bindi was a symbol of marriage and commitment for life in ancient India, which was known as the “golden bird” due to its vast gold reserves. Tikuli art during the Mughal rule transformed into a luxurious form of expression, symbolizing class and royalty. Bihar became a hub for this exquisite art, with traders from far-off states to Patna purchasing intricate gold and silver foil designs.

However, as machine-made goods took over during industrialization, the handmade beauty of Tikuli began to vanish. The more detailed the design, the higher its value. By 1900, the Tikuli art was facing the threat of extinction. In 1954, Chitracharya Padmashree Upendra Maharathi, a painter, artist, and designer, provided a new dimension to the Tikuli art by adopting the Japanese method to portray the dying Tikuli art on glazed hardboard.

Traditionally, Tikuli paintings were made using glass as a canvas. The artist would shape the glass like a balloon and paste gold foil on it, painting over it with delicate and intricate motifs using natural colors and enamel. These artworks, deeply influenced by the styles of Madhubani painting, often featured mythological themes, folklore, and scenes from daily life. The use of strong outlines and bold colors like red, blue, yellow, white, and black gives Tikuli art its distinct identity.

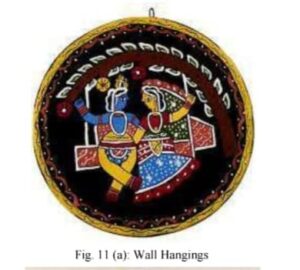

However, due to the high cost and fragility of glass, the craft underwent a transformation in recent years. Modern Tikuli artists have adapted the art form onto more durable and cost-effective materials like hardboard and MDF (Medium Density Fibreboard), which not only makes the art more accessible but also opens up creative applications such as decorative plates, coasters, wall hangings, and table mats.

The unorganized and largely rural nature of the Tikuli sector, along with outdated production methods, low availability of raw materials, and limited market access, have all contributed to its decline. Indian handicrafts are a unique part of India’s cultural fabric, with their vast, vibrant, colorful, and simple yet graceful charm making them a unique part of India’s cultural fabric.

HISTORY

A bindi is a traditional forehead decoration worn in South Asia, particularly in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Mauritius. It is a bright red dot applied in the center of the forehead near the eyebrows, symbolizing the sixth chakra, ajna, the seat of “concealed wisdom.” The bindi is believed to retain energy and strengthen concentration, and represents the third eye. According to the Jabala Upanishad, Avimukta (the middle of the eyebrows) is the abode of Brahman in all beings.

Bindis were created from Vedic times to worship one’s intellect, and were used by both men and women. The belief was that on the bindi, a strong individual, family, and society could be formed. Traditional bindis are red or maroon in color, and can be made by applying vermilion powder with a fingertip. For beginners, a small annular disc can be used. Various materials, such as sandal, ‘aguru’, ‘kasturi’, ‘kumkum’, and’sindoor’, can be used to color the dot.

PROCESS

Originally, it involved melting glass, blowing it into a thin sheet and making and adding traced pattern in natural colors and afterwards embellishing it with gold foil and jewels. The gold foil was etched to form traced patterns and later, natural colours were added for enhancing the etched designs. Tikuli were mainly adorned by Queens and Aristocrat women of yore. Jewels were put on gold leaves according to the status of the women in the society and these beautiful hand crafted Bindi’s were a proud possession of women in India.

Later, post British raj and industrialization, machine made bindis replaced Tikuli. For more than a decade there after Tikuli artists were jobless. Many shifted their occupations; others lost their houses. Hence, Shri Upendra Maharathi, a renowned artist then, reestablished the craft in the form of enamel painting on hardboard.

The base was prepared out of wood which was coated and smoothed using sand paper 4-5 times till the base was a dark brown/black glistening surface like polished granite. Now ready to be embellished using enamel paint and a fine sable/squirrel hair brush, it was painted by women in single strokes in a complimentary colour scheme using primary colors to create a piece of art.

Themes, shapes, colour schemes and style of composition have seen changes since then. Since, enamel paint makes the surface heat proof and water proof, making utilitarian items like coasters, trays and mobile stands have been practiced.

WHAT MAKES A CRAFT “LANGUISHING”?

A craft is considered to be languishing if it meets these three conditions:

- The total number of active artisans is fewer than 25.

- Most artisans no longer practice the craft full-time or depend on it for a living.

- Young people from artisan families are not learning the craft, leading to a generational gap.

These conditions are sadly true for many traditional Indian crafts, including Tikuli.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF TIKULI ART

Tikuli is a unique form of hand painting that originated in Patna, Bihar, over 800 years ago. It holds a special place in the history of eastern India’s artistic traditions. Originally made with natural materials and delicate designs, Tikuli art was once a thriving craft. But over time, it has lost its presence in the mainstream and now struggles to stay relevant in the modern world.

CULTURAL RELEVANCE AND ARTISTIC ELEMENTS

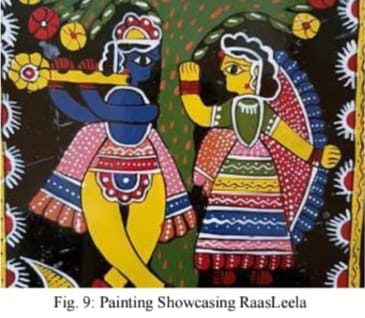

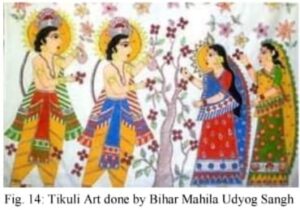

Tikuli art holds a mirror to the cultural fabric of Bihar. Much like its cousin, the Madhubani painting, it reflects the spiritual consciousness of the region. Common themes include tales from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, village scenes, festivals, and divine motifs of gods and goddesses. However, Tikuli art is more decorative in nature and less narrative than Madhubani.

Artists use vibrant, glossy colors and precise detailing to create symmetrical and floral patterns. The finesse required in Tikuli painting is extraordinary, and it often takes seven to ten days to complete a piece. In this regard, Tikuli art is not merely a form of painting but a meditative practice, passed down through generations by oral tradition and hands-on mentorship.

THEN VS. NOW: TRADITIONAL VS. MODERN TIKULI ART

Earlier, Tikuli art was practiced by both men and women. The materials used were natural, costly, and elegant, producing sophisticated pieces that required both time and specialized skills. The themes were often mythological or royal, with great attention to detail.

In contrast, the modern version of Tikuli painting is largely practiced by women who now use enamel paints and synthetic boards. The contemporary version, while still beautiful, focuses more on accessibility and affordability. Today’s Tikuli art is lighter, cheaper, and mass-produced—helping it reach more people but also losing some of its original intricacy and charm. Many modern themes are now inspired by Madhubani art, another popular folk style from Bihar.

UNIQUE VISUAL IDENTITY OF TIKULI ART

Tikuli art is known for its:

- Bold and colorful visuals.

- Use of enamel paints with a glossy surface.

- Folk themes and hand-painted details.

- Black and white outlines.

- Flat, realistic depictions without perspective.

- Stylized figures and motifs.

- Intricate, detailed elements referred to as “Sa-jaawat”.

THE DECLINE AND THE CRISIS

Despite its beauty and cultural importance, Tikuli art saw a steady decline with the advent of industrialization and the flood of cheap, mass-produced decorative goods. Many traditional artists were forced to abandon the craft in search of more stable income sources. It gradually became a dying art, practiced by only a handful of artisans in Bihar.

The situation worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bihar’s craft sector, like many others across India, was hit hard by lockdowns and economic disruptions. The closure of local markets and art fairs such as the Shilpgram in Patna meant artists could neither sell their goods nor procure essential raw materials. For nearly three months, orders were halted, and artisans were left unemployed.

In particular, the artists who specialized in Tikuli art had to halt production due to the unavailability of chemical paints and glass. Some had to fall back on natural dyes and pigments, reviving the traditional techniques once used by their ancestors. According to surveys conducted during this period, nearly 85% of craftspeople faced difficulties in raw material procurement and had no access to microloans. Additionally, many faced order cancellations, delayed payments, and income reduction, with 70% reporting a significant drop in earnings.

TIKULI’S COMEBACK: REVIVAL EFFORTS

However, as history often shows, adversity can spark innovation. The artists of Bihar, particularly those involved in painting-based crafts, took adaptive measures during the pandemic. One of the most notable innovations was the creation of face masks adorned with Tikuli and Madhubani designs. These handmade masks not only served a functional purpose but also brought attention to traditional crafts in a new form. They became popular both for their artistry and their message of cultural resilience.

Craftspeople also started exploring digital platforms and social media to showcase their work. Influencers and local online businesses helped in increasing visibility and generating interest in these traditional art forms. Virtual exhibitions, Instagram sales, and WhatsApp marketing became new lifelines for the artists.

The pandemic also allowed artists to stay home and involve younger generations in the craft. Working together as families, many children began learning Tikuli painting, preserving the knowledge for the future. The combination of modern materials, traditional methods, and digital outreach helped revive interest in this beautiful art form.

According to the UN, artisanship has dropped by 30% in the past three decades, raising alarm about the loss of cultural heritage and livelihoods. The decline of Mughal influence left many artisans jobless, especially with machine-made goods dominating the market by 1900. Tikuli was nearly extinct.

But a fresh wave of revival began in the 1980s. A group of committed artists, especially Upendra Maharathi, an artist and designer, led this change. Inspired by Japanese hardboard techniques, Maharathi infused new life into Tikuli art. His works, often themed around the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, became a new language for this craft.

He also helped establish an institute, the Upendra Maharathi Shilp Anusandhan Sansthan, in 1956, to support traditional artists. It became a platform for training, promotion, and global recognition of Tikuli artists. Some even participated in Asian art festivals and exhibitions during the 1980s, showcasing Tikuli to the world.

Today, Tikuli art is finding its way back into the hearts and homes of art lovers. Government initiatives like “Vocal for Local” and “Atmanirbhar Bharat” are playing a role in supporting indigenous crafts, including Tikuli. Exhibitions, emporiums, and fairs are again becoming active, and there is a growing appreciation for handmade, eco-friendly, and culturally significant products.

Institutions like the Bihar Livelihood Promotion Society (BRLPS) have also taken steps to support artisans through microenterprises like the Mahila Producer Company Limited, which connects women artisans with buyers and markets. Patna’s Shilpgram has emerged as a key hub for the revival of regional crafts, including Tikuli.

Nevertheless, challenges remain. The craft still needs structured support in terms of raw material supply chains, market linkages, and financial assistance. Policy-level interventions like formalizing artisan cooperatives, offering microloans, and organizing regular workshops can go a long way in ensuring that Tikuli art not only survives but thrives in the coming years.

IMPACT OF UPENDRA MAHARATHI SHILP ANUSANDHAN SANSTHAN

This institute played a huge role in promoting and preserving Tikuli art and other crafts from Bihar. It created awareness through exhibitions, permanent collections, and by establishing a museum. This museum does more than just showcase handicrafts—it offers workshops, encourages young artisans, and even connects rural artisans to stable markets.

In rural areas of Bihar, many artisans live in poverty despite producing exceptional work. The institute runs six-month training courses for youth, teaching both technical and entrepreneurial skills. Students learn not just how to craft, but also how to market and sell their work. The institute also maintains a rich library and offers hostel facilities to students.

GOVERNMENT ROLE IN PROMOTING TIKULI ART

Organizations like the National Institute of Design (NID) have worked under India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry to support traditional crafts. Schemes like the MSME (Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises) cluster development have funded many projects. For instance, a project worth ₹25 lakh was sanctioned in Bihar to promote Tikuli art.

Most Tikuli artisans work in unorganized sectors. These clusters are micro-scale and often lack formal registration. In one such cluster, the gender ratio was stark: 25 women to every man, highlighting its female-dominated nature.

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND OF ARTISANS

Here are some insights into the artisans’ lives:

- Literacy rates are high—around 90% for men and 50% for women.

- 90% of women artisans are homemakers.

- 50% of single women are engaged in part-time or job-based household work.

To empower them, designers are brought in by government bodies to train artisans in innovation, design thinking, and product development. Workshops generally last 1–5 days and aim to spark new ideas and solutions for market challenges.

MATERIALS USED IN TIKULI ART

Tikuli artists typically use:

Wood and MDF: Medium-density and high-density boards for coasters and wall

paintings.

Enamel Paint: Glossy and durable, used in a two-layer process.

Thinner: To adjust paint consistency.

Brushes: Fine brushes (up to size 30) for precision.

Colour Palettes: Used to mix and hold colors.

Tracing Paper: For detailed design outlines.

Cotton Cloth: For cleaning.

All raw materials are locally sourced, supporting both cost-effectiveness and

sustainability.

LIST OF RAW MATERIALS

WOOD

Medium density & High density fibre boards (MDF/HDF)

Coasters and wall paintings are usually made on coated medium density and high density fibre

boards.

Source: Through whole sellers and suppliers within Patna. It is provided by the contractor.

PLY BOARD

Coaster stands, trays, mobile stands and boxes are made of ply board.

Source: Through whole sellers and suppliers within Patna. It is provided by the contractor.

WOOD FILLINGS

Edges and surfaces crevices coaster stand, trays, mobile stands and boxes are finished using

wood fillings (dust)

Source: Waste from cutting ply board and HDF/MDF.

ENAMEL PAINT

Enamel paint is used to prepare base coat and main ornamentation process. Asian paints enamel

paint is used.

Source: Through whole seller within Patna. Paint is provided by the contractor.

THINNER/ ASTRINGENT

It is used to dilute the enamel paint to achieve the right consistency for painting and also to

clean excess paint and the used Brushes

Source: Through whole sellers within Patna. It is provided by the contractor

BRUSHES & COLOUR PALETTE

0, 00, 000 round Brushes are used for painting whereas flat brushes up to number 30 is used

for preparing the base coat. Plastic small colour palettes are used to mix colours.

Source: Through whole sellers in Kolkata through vendors or is purchased locally. It is

purchased by the crafts women themselves from the assistance of the contractor.

TRACING PAPER

It is used for tracing the design during replication.

Source: Through whole sellers in bulk and later divided within the group.

CLEANING CLOTH

Cotton fabric (preferably knitted) is required to clean Brushes and excess paint.

Source: Waste fabric from households are reused. It is craft women’s own.

RAW MATERIALS FOR FRAMING

Raw materials like Three ply nylon loop, thin cotton fabric and Fevibond is locally source.

The TIKULI CRAFT PROCESS

Creating Tikuli art is no easy task. It requires tremendous attention to detail and patience. The process begins by cutting hardboards into various sizes. Artists then draw sharp outlines with precision, usually in one fluid stroke to ensure neatness.

Once the base is prepared, multiple coats of enamel paint are applied. The final piece is glossy, vibrant, and deeply expressive. Though it takes time, the result is a timeless work of art that holds both aesthetic and cultural value.

Designs and Themes

Tikuli art draws inspiration from the renowned Madhubani style, widely practiced in Bihar and Jharkhand. The motifs reflect eastern Indian traditions—weddings, festivals like Chhath Puja, Deepawali, and stories from epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata. These rich cultural

elements breathe life into Tikuli pieces.

Product Variety

Tikuli art isn’t limited to traditional forms. It’s now applied to lifestyle products such as mobile holders, coasters, trays, and wall hangings. Sizes range from compact squares to larger rectangles, making the craft both decorative and functional.

Raw Material and Storage

Materials used in Tikuli art are handled with care. Once procured, they are stored properly to maintain quality. Artisans follow safety measures while handling enamel paints, wooden bases, and other essentials to ensure consistent production standards.

Eco-Friendly Waste Management

Tikuli production generates minimal waste. Enamel paint left to dry is the primary residue. Even that is dealt with responsibly—wood cuttings are sent to factories for reuse, and wornout tracing papers are recycled. Nothing goes to waste unnecessarily.

Market Reach

Tikuli art has found markets both within India and abroad. Online platforms and exhibitions play a huge role in promoting it. Some unique pieces are now seen in galleries and are collected by art lovers globally.

Challenges to Production

1. Geographical and Climatic Limitations: – Enamel work needs dry conditions and good

lighting. Monsoons and poor ventilation hinder production. The craft also requires dustfree spaces, often hard to maintain.

2. Social and Cultural Shifts: – Originally made by men, Tikuli is now largely done by women at home due to cost constraints. While this makes it more accessible, it also leads to limited workspaces, cheap tools, and reduced quality and output.

3. Political Factors: – Government support influences the craft significantly. Policies for promotion or neglect directly impact Tikuli artisans and their economic stability.

SWOT ANALYSIS

Strengths:

Tikuli items are waterproof, lightweight, and durable. Skilled artisans make the creative

process efficient despite the intricate work.

Resistant to heat and water.

Lightweight.

Bright and colourful.

Available in multiple sizes.

Quick to produce.

Craftsmen are trained.

Unique due to enamel paint usage and creative composition.

Weaknesses:

Only non-organic, synthetic colors are used, many influenced by Madhubani styles. About half the designs and themes are outsourced, which limits originality. The base materials are often

limited, and the variety of products is restricted.

Use of non-organic, chemical-based paint.

Typically uses a single base color.

Heavy influence from Madhubani themes.

Half of the production process is outsourced.

Limited color palette and base materials.

Difficult to adapt designs to 3D forms.

Low diversity in product types.

Market restricted to low-price segments.

Absence of luxury offerings.

Lack of structured skill development programs.

Opportunities:

There is untapped potential in luxury and modern lifestyle markets. Researchers suggest

introducing machines and new techniques without compromising traditional beauty to scale

production.

Introduction of new product lines.

Revival of traditional art styles.

Experimentation with new color combinations and designs.

Usage of a wider color spectrum.

Typography and nameplate creation with enamel paints.

Exploring alternative base materials

Threats:

Modern trends often overshadow traditional crafts. Low returns force artisans to leave the

practice. Unless revived and modernized, Tikuli risks fading out.

Toxicity of paint poses export limitations.

Competition from other Indian art forms.

Rising prices may reduce market demand.

Skilled girls may stop practicing after marriage due to relocation.

WHY REVIVAL IS NEEDED

Tikuli is a symbol of India’s artistic richness. The intricate designs and mythological themes

appeal to global markets. The craft speaks of cultural pride and deserves support. Institutions

like Shilp Anusandhan Sansthan and Bihar Mahila Udyog Sangh have played crucial roles in

keeping it alive. But more needs to be done.

GOALS AND STRATEGIES

The objective is to uplift artisans economically and socially by:

Analysing strengths and weaknesses of the art.

Removing the middleman.

Providing better infrastructure.

Introducing new tools and design techniques.

DESIGN INNOVATION

Originally crafted on hardboard, Tikuli art has adapted to newer materials without harming

tradition. It now extends to men’s lifestyle accessories like ascots and ties, opening the door to

premium markets. These modern applications are still largely unexplored.

FINDINGS

Designers can play a crucial role in reviving Tikuli art by acting as facilitators between the

market and artisans. They help bridge the gap by introducing traditional skills to modern design

requirements, enabling artisans to adapt to changing consumer preferences. Quotes from

scholars emphasize the importance of designers in connecting heritage with contemporary

needs.

DIGHA CLUSTER

Tools & Techniques

The tools and techniques used in Tikuli Art by artisans in the Digha cluster are the same as